The DeWitt Wallace Institute of Psychiatry: History, Policy, and the Arts is an interdisciplinary research unit in the Department of Psychiatry of the Joan and Sanford I. Weill Medical College of Cornell University and New York-Presbyterian Hospital. Its mission is to support, carry out, and advise scholarship in a broad range of issues relevant to the present day theory and practice of psychiatry. Since its inception in 1958, the Institute has sought to use in-depth studies of the past to enhance understanding of the many complex matters that surround contemporary thinking and practice regarding mental health and illness. Over the last few decades, Institute faculty have made critical contributions to debates surrounding matters like de-institutionalization, the history of the mind-brain problem, stereotyping, the scientific status of psychoanalysis, and the conceptual origins of different forms of mental illness.

Leadership

The Institute has been directed since 1996 by the scholar and psychiatrist Dr. George Makari, under whom it has branched out beyond history to foster studies at the interface of the “psy” sciences (e.g., psychiatry, psychoanalysis, and psychology) and the humanities, including explorations of the arts [link to psychiatry and the arts page], medical ethics, and mental health policy. Thanks to Dr. Megan Wolff, the Institute has taken up the responsibility to create fact sheets to help inform public debate on the many pressing mental health issues that face us today, from the relationship of psychiatric illness to homelessness and gun violence, to the opioid overdose crisis and the incarceration of the mentally ill.

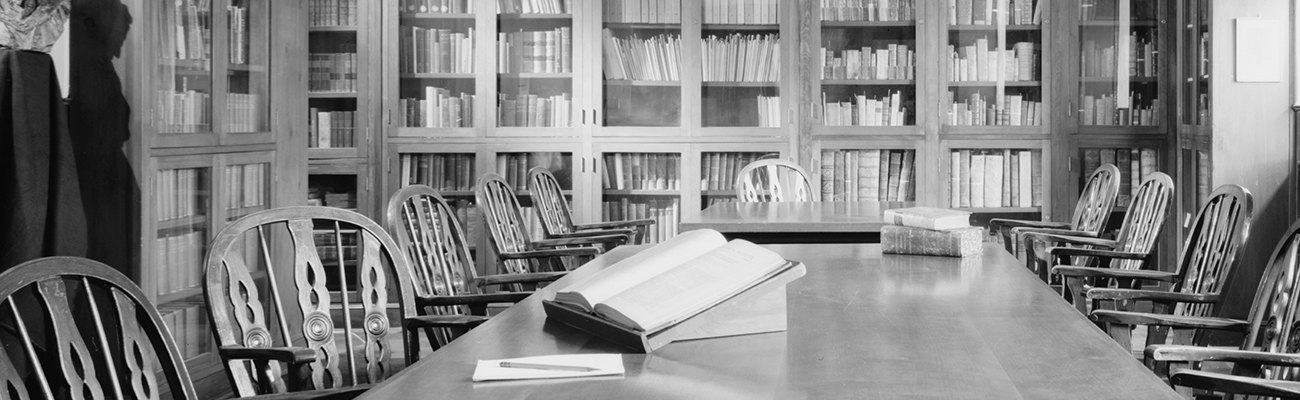

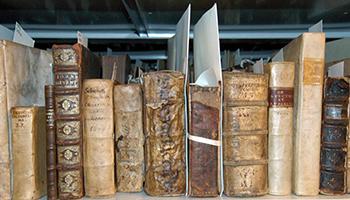

Oskar Diethelem Library

All of these scholarly efforts are deeply enriched by the Oskar Diethelm Library, under the stewardship of Nicole Topich, MLIS. Opened in 1936, the Diethelm is the library of record for American psychiatry, and one of the greatest such collections in the world. Its more than 35,000 volumes in Latin, English, German, French and more, commence with incunabula on witches and humours from the 15th century and end with yesterday’s discovery on neurotransmitters. In addition to its unsurpassed collection of printed matter, the library is the repository of manuscript collections from critical individuals and numerous organizations. We are honored to host researchers from near and far who seek to extract the innumerable untold stories and lessons that lie in this treasure trove.

Richardson Seminar on the History of Psychiatry

The Institute hosts the Richardson Seminar on the History of Psychiatry, the longest running colloquium of its type in the United States. It convenes working groups that bring together researchers in specific domains, a speaker series on Mental Health Policy, and various educational activities for students. With an open atmosphere that draws a mix of psychiatrists, psychologists, psychoanalysts, historians, ethicists, literary critics, and others, the Institute hopes to bridge studies of the past with the science of the future, and connect the domains of science and the humanities, a necessity if our understanding of ourselves is to encompass our overwhelming mix of genes, neurons, brains, minds, selves, families, and societies.

Oskar Diethelm, M.D.

The Institute’s foundation was laid in 1936 with the arrival of Dr. Oskar Diethelm to the Payne Whitney Clinic. Diethelm was a staunch bibliophile, and he noted almost immediately that there were fewer than 100 books available at his new work site. Using his position as the newly-appointed Chair of the Department of Psychiatry, he lobbied the Board of Trustees to acquire more. His principal argument was that one could not practice psychiatry well without an appreciation of the history and the development of its theories and techniques. Persuaded, the Board allocated funds for the creation of an historical library within the psychiatric clinic. Diethelm augmented it. Each summer he travelled to Europe to survey the holdings of the chief university medical schools and libraries. In France, Germany, Switzerland, Italy, and Spain, Diethelm purchased texts at used book stalls to send back to Payne Whitney, which soon boasted a distinct collection of rare books and manuscripts. Its holdings came to include nearly all of the psychiatric classics and a growing collection of early doctoral dissertations, making the Clinic’s new library a formidable resource in the history of psychiatry, one of the only such repositories in the United States.

Oskar Diethelm brought more than an interest in books to the culture of the Payne Whitney Clinic. He also introduced a change in the way that scholars thought about medicine and history, one that had been sweeping across Europe for decades. As the feverish pace of scientific discovery had begun to slow, medicine was becoming more self-reflective. Since 1900, new libraries, societies, and international congresses emerged across the Continent, and the creation of new journals and even professorships marked the maturation of the field. Development was somewhat slower in the United States, but when the first American Institute for the History of Medicine was founded at Johns Hopkins in 1929, Oskar Diethelm was present to witness it.

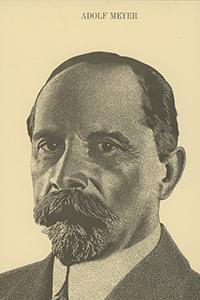

Influence of Adolf Meyer, M.D.

From 1925 to 1936, Diethelm studied under Adolf Meyer, at the Phipps Clinic at Johns Hopkins. The two men had much in common. Both were natives of Switzerland and possessed the hallmarks of European humanism: a sophisticated knowledge of intellectual history, a wide-ranging interest in politics, history, and culture, and a patrician reverence for books. In 1932, Henry Sigerist, another denizen of Switzerland and one of the brightest lights of medical history in Europe, assumed the directorship of the new Medical History Institute at Hopkins. That historian’s intellectual approach and methods fit neatly with those of Diethelm and Meyer, and his personal charm and acumen attracted numerous students. Sigerist believed fervently that medical history could serve as a bridge between science and the humanities, and that it could throw light on present practices. “History,” he noted, “will make the modern physician aware that his medicine is not the product of recent decades but rather the result of a long and troubled development, and that our grains of truth emerged from a sea of errors, a sea we are still wading in.” It was an attitude which set the tone for the discipline’s development in the United States, and one that Diethelm would carry with him to Payne Whitney.

As Sigerist set about building up a new historical library at Hopkins, he turned for advice to his colleagues. Adolf Meyer possessed a personal library of psychiatric literature so extensive that he and his student were promptly called upon to help, and Oskar Diethelm found himself pressed into service purchasing and arranging the library’s psychiatric section. He realized as he did so that no collection existed at any university or medical center that did justice to the history of psychiatry. It was a deficiency that he would work to remedy for the rest of his life.

Eric T. Carlson, M.D.

Guided by Oskar Diethelm, by 1953 the historical collection at Payne Whitney had blossomed into an attractive, wood-lined library with rare books in glass-enclosed cases and an eager clientele. Interest in the history of medicine was growing nationwide, and in 1958, the National Institute for Mental Health announced a series of grants to support research in the field. Eric T. Carlson, a student of Oskar Diethelm’s, successfully applied for one of these grants, obtaining the seed money that would formally launch the Section on the History of Psychiatry and the Behavioral Sciences at Payne Whitney. The grant aimed to promote “the study of the development of psychiatric thought in America,” and provided enough funds for a researcher and for a part-time Section director. Diethelm appointed Carlson to the new Directorship, a position he would hold until his death 34 years later.

The History Section opened with a flurry of activity. After consulting with prominent Columbia historian Richard Hofstadter, Carlson took steps to create an atmosphere of interdisciplinary collaboration. He used the money obtained from the NIMH grant to recruit Norman Dain, one of Hofstadter’s promising graduate students, as a research assistant. Based on a nucleus composed of Carlson, Dain, and the young psychiatrist Jacques Quen, the cluster of half a dozen scholars and researchers who gathered every other week soon grew to a body of regular seminar attendees. Their research projects developed into academic journal articles and a number of seminal books in the field. For Dr. Carlson, one of the primary goals of the section and its work was to connect isolated scholars. The seminar offered a venue for communication and collaboration. At the 1959 American Psychiatric Association meeting, attendees discussed founding a newsletter on psychiatric history. Soon thereafter, Carlson took on the project himself, launching the History of the Behavioral Sciences Newsletter in 1960. The newsletter was so successful that in 1965 it became the Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences, a peer-reviewed organ that thrives to this day.

When Dr. Diethelm retired in 1962, colleagues named the rare books library in his honor. The collection had grown enormously. In addition to Diethelm’s assemblage of British and American works from the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries, it now included items dating from the 15th century in Latin, French, German and Italian, and selected works in Arabic, Dutch, Hungarian, Portuguese, Russian, Spanish, and Swedish. It had begun to reach its founder’s goal as the preeminent collection on the history of psychiatry.

New Archival Collections

To widen the library’s circle of supporters, Dr. Carlson launched the “Friends of the Oskar Diethelm Historical Library” in 1964. The appeal prompted donors to establish a significant fund for the acquisition of manuscript and archival material two years later -- the first private gift of special funding. Carlson regarded the contribution as a milestone in the library’s development, and in recognition he presented his own collection of manuscripts to the library. In the years that followed, acquisitions of unpublished materials gained momentum, and the library began receiving archival collections from bodies such as the American Foundation for Mental Hygiene, and from individuals such as Donald Winnicott, Herbert Spencer, Thomas Salmon, and S. Weir Mitchell.

In 1966, the merger of the Westchester Division (formerly the Bloomingdale Asylum) and the Payne Whitney Clinic brought the historical books of the Division to the shelves of the Diethelm Library. Because the Bloomingdale library had been in operation since 1823, the accession made the Oskar Diethelm Historical Library the oldest collection of psychiatric literature in the country.

1970-1990

The decades that followed were enormously productive ones. Active participant Jacques Quen, who for years had mentored fellows, residents, and medical students with an interest in the history of psychiatry, became Associate Director in 1971. The following year, a grant from the Josiah Macy Jr. Foundation made possible a pair of dedicated lecture series, one on “The Historical Development of the Mind-Body Problem” and the other a two-year program on the work of Adolf Meyer. At the completion of the second series, the Director and Associate Director edited and published American Psychoanalysis, Origins and Development: The Adolf Meyer Seminars. In the meantime, Norman Dain, who had studied with Ted Carlson as a young person, was becoming one of the most em¬inent historians of American psychiatry in the country, and in 1975 the Section honored him with a faculty appointment, making Dain the first historian in a Department of Psychiatry. He was joined in the distinction in 1978, when Sander L. Gilman, then a prominent academic at Cornell’s Ithaca campus, also received an appointment. Having arrived in 1977 for a sabbatical year with the Section, Dr. Gilman completed Seeing the Insane, a landmark book on the history of psychiatry and visual imagery, and began research on the concepts of degeneration, sexuality, and stereotyping, which would later be another hallmark of his scholarship.

In 1979, a move to larger and more attractive quarters on the ninth floor of the Payne Whitney Clinic further facilitated research activities. Additional conferences, grants, and acquisitions continued to enhance the activities of the Section. A 1984 symposium held at Bear Mountain, NY, yielded a volume entitled Split Minds/Split Brains: Historical and Current Perspectives, once again edited by Jacques Quen. In 1985, a gift from noted psychoanalyst and historian Mark Kanzer enabled the participation of a series of research fellows, who took up residence at the library while in pursuit of their doctorates. Dubbed the Carlson Predoctoral Fellowship, the funds supported the early work of sholars like Leonard Groopman, Daniel Burston, Jan Goldstein, and John Efron.

New Beginnings in the 1990s

A series of challenges followed, which ultimately resulted in a number of new beginnings. The sudden death of Founding Director Eric Carlson in January, 1992, brought with it a period of loss and reorganization. Jacques Quen took charge as Acting Director and formalized a steering committee that Dr. Carlson had once created for the discussion of policy issues. The “policy group” had much to consider. A major modernization project at New York Hospital anticipated the tearing down of Payne Whitney in 1994. A new space would have to be planned for the Library and its associated programs, a new director appointed, and a new permanence sought. The death of Oskar Diethelm in 1993 provided further opportunity for taking stock, and so a site visit was initiated that year to consider the major questions about the Section’s future.

In their report, evaluators Gert Brieger, Gerald Grob, and Stanley Jackson found that the past seminars and future potential of the Section and its now unrivaled library dwarfed the uncertainties of the present moment. Psychiatry, they noted, had much to gain from an understanding of its history, and they strongly recommended reinforcing the future of the section.

Toward that end, a recent research fellow, Dr. George Makari, was appointed Acting Director and tasked with strengthening the Section. A full-time librarian was hired for the first time. With the tearing down of Payne Whitney, the collection moved temporarily to quarters at the New York Academy of Medicine, where it took up a mile of borrowed shelf space. A grant obtained during this period enabled the books to be cataloged online, and the process of doing so revealed that a large proportion of them were invaluable and extremely rare. Many proved to be the only copies in the United States. It became clear that the Oskar Diethelm Library was the finest such collection in the nation.

While the collection sojourned uptown, the Section on the History of Psychiatry continued its research seminars at Cornell Medical College. “As the History of Psychiatry Section became less a concrete place and more of an idea, our research and educational mission became more defined,” remarked Dr. Makari. Benefactors Frank and Nancy Richardson agreed. In 1994, they created an endowment to support the now-renamed Richardson Seminars on the History of Psychiatry. A year later, funds raised in memory of Ted Carlson supported Dr. Makari’s inauguration of the Eric T. Carlson Memorial Grand Rounds. The Lecture honors lifetime achievement and has showcased the work of scholars such as Roy Porter, Charles Rosenberg, Nancy Tomes, and Ian Hacking. In 1995, Dr. Makari and Professor Sander Gilman initi-ated a monograph series, the Cornell Studies in the History of Psychiatry. A year later, Dr. Makari was appointed Director of the Section, just in time to help with the planning for the new library space. When the collection moved into its new accommodations in the Baker Tower in 1999, it relocated into a centralized, fully modernized state of the art facility, staffed with an archivist and, for the first time, a professional administrator.

The DeWitt Wallace Institute of Psychiatry: History, Policy, and the Arts

Since then, the Section’s collection, its mission, and its name have continued to grow. In 2009, in grateful recognition of longstanding support by The DeWitt Wallace Foundation, the Institute became The DeWitt Wallace Institute for the History of Psychiatry. Ten years later it changed again, to the DeWitt Wallace Institute of Psychiatry: History, Policy, and the Arts. This latest change largely served as a recognition of the increased scope of the Institute’s undertakings, which now stretched well beyond the examination of history. At the Oskar Diethelm Library and its associated seminars, study of the past intersected with the present.

The Institute’s programming told the story. The tradition of supporting research fellows had been rejuvenated in 2008 with the establishment of the Benjamin Rush Scholars Program, open to psychiatry residents with an interest in the history of the field. Working groups on the history of the mind sciences, on psychoanalysis and the arts, on narrative psychiatry, and on the interaction of the “psy” disciplines with society drew interdisciplinary scholars to a range of topics touching on the significance of psychiatry in everyday life. In 2013, the launch of an initiative on Mental Health Policy brought scholars and practitioners together to utilize history as a lens to inform policy. In the fall of 2020, the Institute added a new seminar on Psychiatry and the Arts, a series of talks and interviews between prominent authors, musicians, and artists and Institute Director George Makari.

The Institute continues to expand in fulfillment of its mission to bridge the past and the future, and to cross from science to the humanities -- all this in order to better understand the mind, the brain, and the individual complexities that come with embodied psychic life. The Diethelm Library’s ever-expanding wealth of archival material such as personal papers, institutional records, and ephemera continues to grow; it presently holds the archives of over sixteen organizations in American psychiatry, including the American Psychoanalytic Association, and can be con¬sidered the library of record for American behavioral science.

It might be argued that in the 21st century, the Institute of Psychiatry has fulfilled Dr. Diethelm’s dream. The Institute serves as an unusual academic center, an invaluable and irreplaceable resource for a world-wide network of researchers. It is a unique forum, crossing disciplinary borders to deepen our understanding of what makes mental life and what determines its ills. Thanks to the efforts of its many supporters, the Institute today is a center for scholarly collaboration, research and the preservation of significant works, unrivaled by any other facility in the academic world.